Serendipitous conversation brought an engineer and two surgeons together to develop Intelligent Mouthguard made from technology created by Cleveland Clinic researchers.

Adam Bartsch was two years into his PhD program in mechanical engineering at Cleveland Clinic when a meeting in the cafeteria set something remarkable in motion.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/4765a2ad-393c-4e50-b1a0-2385a239c483/bartsch-adam-headshot)

Adam Bartsch, PhD

Spine surgeon Edward Benzel, MD, introduced Dr. Bartsch to his spine fellow, neurological surgeon Vince Miele, MD, and said, “you guys should talk.”

This discussion ultimately led to the creation of an innovative mouthguard that makes rugby safer for players today.

At that time, Dr. Miele was an amateur boxer. He also served as a ring-side physician, monitoring boxers during matches for head injuries.

Dr. Bartsch was helping neurosurgery residents and fellows conduct experiments on the spine. And he also had several research projects under his belt on concussion and mild traumatic brain injury.

Dr. Benzel says introducing them was a no-brainer.

He thought they could all work together to create a device that could monitor head impacts and send an alert if a concussion assessment was needed.

Together, they formed a kind of innovation powerhouse.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/b3f2c103-5957-4e0b-9a68-06e9a34286af/miele-vincent-headshot)

Vince Miele, MD

Dr. Bartsch brought engineering insight, Dr. Miele contributed real-world athletic knowledge and surgical skill, while Dr. Benzel brought academic and scientific prowess.

“We combined forces to challenge each other, think things out and capitalize on each other’s strengths,” Dr. Benzel says.

In 2010, the trio (with support from others in our Neurological and Lerner Research Institutes) developed the “smart guard” technology.

Today, this technology is used by Prevent Biometrics in its “Intelligent Mouthguard” (IMG) system.

Last fall, World Rugby selected the IMG system for global adoption by its 7,500 professional women and men athletes.

The technology uses sensors to record impacts to the athlete’s head and sends reports through Bluetooth wireless transmission to an iPhone.

It collects various data points, such as contact workload, head impact direction and location and linear and angular accelerations.

These help World Rugby clinicians identify an athlete who could benefit from a concussion assessment.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/fbb85d58-8f09-4c93-b4b7-fd7d35bea8ab/white-clear-mg)

There were some twists and turns along the way.

As their research began, the group was assigned a Cleveland Clinic Innovations partner to help guide their work.

Securing funding is necessary to bring a design to life. But prepare for rejection — a lot of it.

Of course, failures will happen during development and design. You must change course and try different approaches when something isn’t working.

The same goes for funding.

“I had so many grant proposals that were rejected after I spent huge amounts of time writing them,” says Dr. Bartsch. “But with every one of the failures, I was learning.”

Money was needed to build prototypes and bring new people on board.

After they secured grant money, they were able to add Sergey Samorezov, senior principal research engineer, to the team.

And with him came much-needed mathematical knowledge.

“He was a key cog in our machine,” says Dr. Bartsch. “He rounded out the team. We now had two engineers and two surgeons.”

The inventors had determined that impact sensors in a mouthguard — rather than say a helmet or head band — was the best method for detecting head accelerations.

Samorezov and Dr. Bartsch developed a robust sensor data processing algorithm and validated it through experiments.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

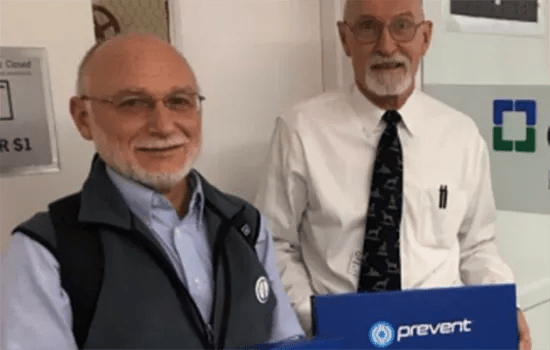

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/f16d00e7-1fe6-4af9-a015-afedb7096f58/Samorezov-Benzel)

Sergey Samorezov and Edward Benzel, MD

They also set up an experimental head impact simulator and measurement system for testing and analysis.

“The big obstacle we faced was to prove to the head impact research community the validity and superiority of our approach, as compared to other methods accepted at the time,” says Samorezov. “Psychological inertia is the hardest one to overcome.”

They published a pivotal study in 2014 that confirmed their findings.

It took several years of technological development to get to a point where Innovations could license the technology to an outside company, who could then turn a conceptually working prototype into a useful and attractive product.

But by 2015, the license was ready.

Prevent Biometrics was formed, and Dr. Bartsch eventually left Cleveland Clinic and went to Minneapolis to work there. Today, he serves as the company’s Chief Science Officer.

Going from an idea to product requires hard work and commitment.

“We recognized we had a good idea, but most good ideas fall by the wayside,” says Dr. Benzel. “We, however, persisted and prevailed.”

Dr. Bartsch agrees: “You need a great idea. And you need to foster an environment that can make that idea happen.”

Listening to others and being resilient are essential.

A little enthusiasm helps, too. “When you have an idea, let your enthusiasm take you to the place you want to be,” says Dr. Benzel.