Ghanaian student Metabel (Metty) Markwei (’22) led the most recent diversity dinner event, sharing insights about her journey to medicine, her journey to the West, her motivations and lessons from taking multiple trips back home to Ghana as well as her experiences navigating being Black in America.

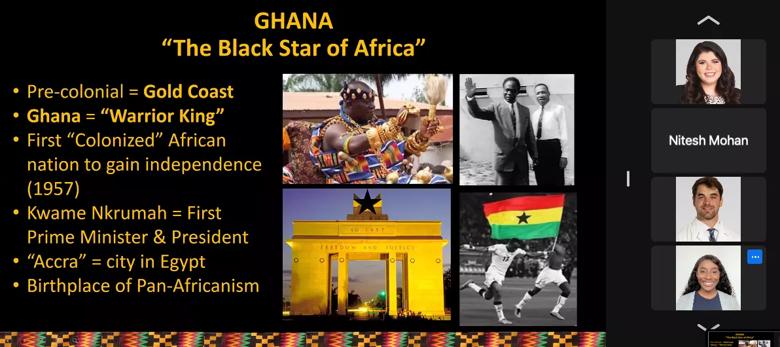

Among the many facts that Metty offered about Ghana, a country in West Africa, is that Ghana is referred to as the “Center of the World.” (Ghana is the country closest to the point where the prime meridian (longitude zero) and equator (latitude zero) intersect. The actual center lies in the ocean, but Ghana is closest to that center.) About the physical size of Oregon, Ghana has a population of 31 million people, which is about 27 million more people than live in Oregon. The country’s population density contributes to some of its major healthcare challenges including accessibility and a critically low doctor-to-patient ratio.

Metty also noted that although clinical trials for the COVID-19 vaccines were held in Africa, Africans were not among the early recipients of the approved vaccines.

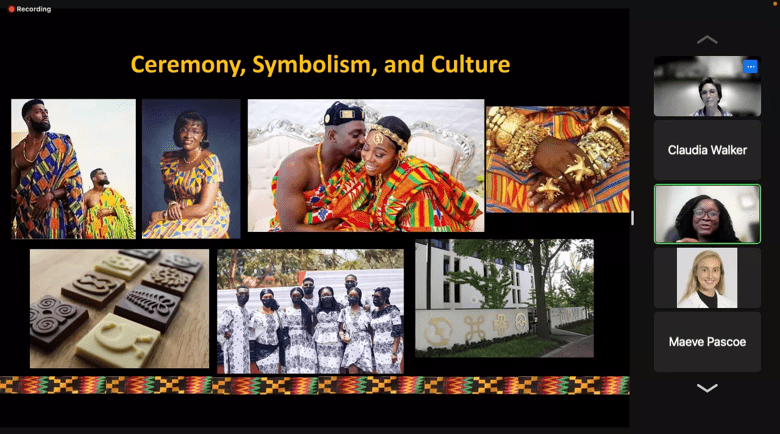

Symbolism is prevalent in Ghanaian culture, particularly around colors, shapes and clothing patterns, all of which carry specific meanings. Because of this, Ghanaians pay special attention to wearing the appropriate outfit for the occasion.

Although the diversity dinner was held virtually, all the participants indulged in a special meal of jollof rice (a typically vegetarian dish) and fried plantains that Metty prepared in her kitchen and served in takeaway containers for students to pick up.

She explained that Nigerians and Ghanaians engage in friendly battles over who makes the best jollof rice. The main difference between the dishes is the type of rice used. Ghanaians tend to use jasmine rice, whereas Nigerians tend to use parboiled rice. The method of cooking the rice in a flavorful tomato sauce varies by chef.

“I personally think the type of rice affects how much flavor the rice can absorb from the stew it is cooked in and, eventually, affects the taste,” Metty later explained. “A hallmark of my time here in America is cooking for large groups of people as a form of bringing people together. I believe ‘food is the language of love.’”

To help draw upon the common threads we as humans share, Metty posed several questions throughout her presentation, including what the participants were hoping to learn, what they are hoping to do with their medical knowledge and what privileges they have been afforded that others do not have. She also asked pertinent questions about allyship and anti-racist efforts to make the community safer for people of color.

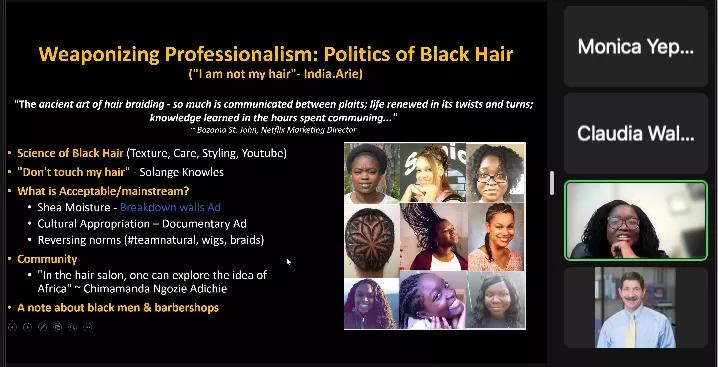

Growing up in Ghana (with a predominantly Black population), Metty was not treated differently because of the color of her skin, something that she has experienced since living in America. She noted the vast diversity of “blackness” in America, from ethnicity and experience to education and socioeconomics. She also spoke of the incredible contributions that Blacks have made to science and medicine. For example, the first Emergency Medical Service (EMS) in America was started by a group of Black male paramedics in the 1960s in response to a lack of emergency service in a minority area in Pittsburgh. Because of its success, the EMS model was adopted nationally by the mid-1970s.

Metty also spoke about the many contributions of Black patients such as Henrietta Lacks, who died in 1951 of cervical cancer and whose cancer cells, named HeLa cells, are still widely used today for medical research, most recently to develop COVID-19 vaccines.

In terms of the cultural considerations of caring for Black patients, Metty urged her classmates to engage in building trust with people of color and minorities because of the medical community’s long history of mistreatment of Black patients.

Metty ended her presentation with this quote by poet and civil rights activist Audre Lorde for the group to reflect upon:

“…we have all been programmed to respond to the human differences between us with fear and loathing and to handle that difference in one of three ways: ignore it, and if that’s not possible, copy it if we think it is dominant, or destroy it if we think it is subordinate. But we have no patterns for relating across our human differences as equals. As a result, those differences have been misnamed and misused in the service of separation and confusion.”

Generally held monthly, diversity dinners allow a student or group of students to showcase their unique culture, with the goal of enhancing appreciation of our differences and finding threads of commonality.

Read “Student Spotlight: Metabel Markwei” to learn more about her.